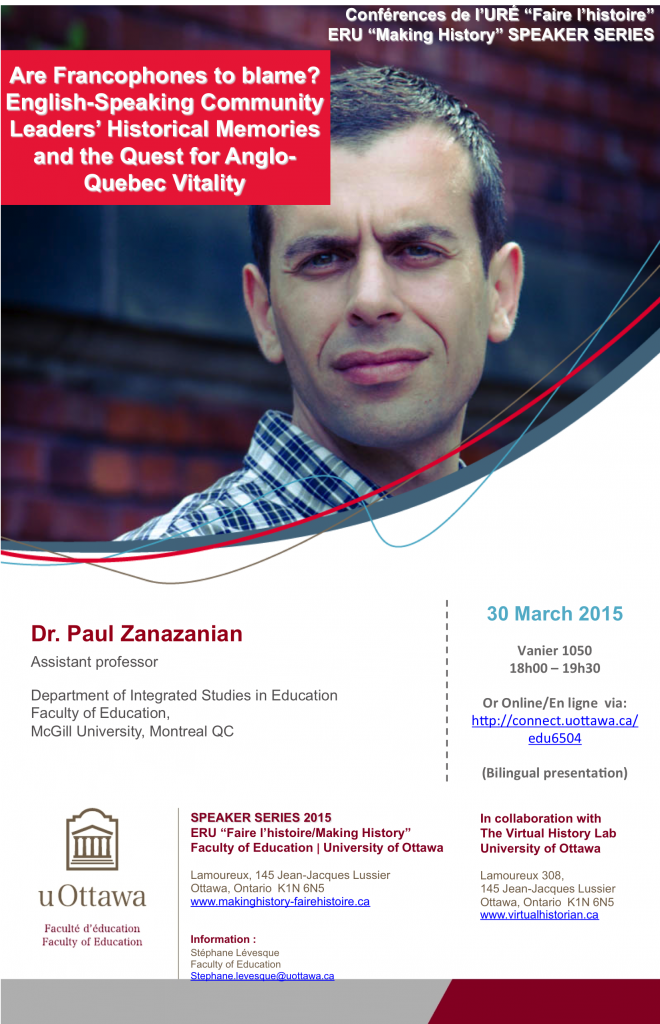

As part of the ERU “Making History” Speaker Series, associate professor with the Faculty of Education at McGill University, Paul Zanazanian, will be discussing the historical memories related to English-speaking community leaders and the ongoing quest for Anglo-Quebec vitality.

Attend in person or participate online: http://connect.uottawa.ca/edu6504

1 0