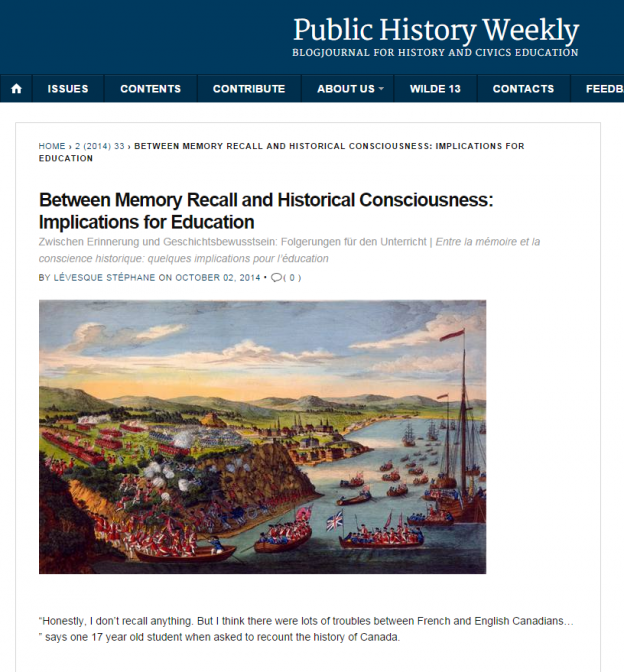

Anxieties about national identity and its strengthening and preservation are common in countries around the world, and it is, of course, entirely natural that this should be so in times of great change, challenge and uncertainty…

Is a Little Knowledge a Dangerous Thing? Young People, National Narratives and History Education. https://t.co/VuZcaqmQBS @samwineburg

— Jocelyn Létourneau (@JocLetourneau) November 26, 2015

1 0

Dans: knowledge of history